Building Globally: A Practical i18n Guide

A practical guide (with lots of examples) for engineers, designers & product managers

Internationalization (i18n) isn’t just a language feature. It’s a design constraint, a code architecture choice, and a product strategy.

For designers, it’s about creating flexible interfaces that adapt to different scripts, lengths, and layouts.

Design Once, Regret Never: The Global UX Guide

Localization is a shape-shifter—it’s an engineering problem right up until the moment it becomes a business growth lever.

For product managers, it’s planning for scale understanding that every new market brings its own linguistic, cultural, and technical expectations.

GTM Isn’t One Strategy. It’s Twelve.

Most GTM strategies are built for speed. Global GTM needs stamina, and a lot more local insight than most companies realize.

For engineers, it means building systems that can handle text direction, plural forms, and locale-aware formatting without breaking.

Get it right early, and your product can travel the world. Get it wrong, and you’ll be rewriting core systems when it’s too late.

Successful teams build internationalization (i18n) before launch, measure after launch, and iterate continuously.

Because each locale is unique, preventing i18n bugs requires more than good intentions. It demands a mix of linguistic intuition, technical know-how, and internationalization expertise.

Below is a consolidated, example-rich checklist you can share with every developer who touches a string file.

Concatenation 🚫 Don’t split sentences

The classic bug

By far, the issue we ran into the most in software localization. Developers will often concatenate strings to make the code more efficient. However, concatenation will likely cause issues with localization.

Let’s look at 1 simple example

“Black” + “cat”

The above will output the phrase Black cat. It’s a perfectly valid line of code using the plus sign (+) to join two strings—but this approach often creates headaches for localization.

When extracting strings for translation, most systems will pick up each individual string separately. In the example above, that means you'll end up with two separate strings—so the translator will see each fragment on its own and be asked to translate them independently, without the full sentence for context.

Translator sees two segments:

“Black” 2. “cat”

In French the order flips → “chat noir”, impossible to produce from separate pieces.

How can we workaround this in localization?

We are either forcing French language to sound weird or contaminating our translation memory database.

A better solution would be to place the entire phrase within one code string:

“Black cat”

A hyperlink example

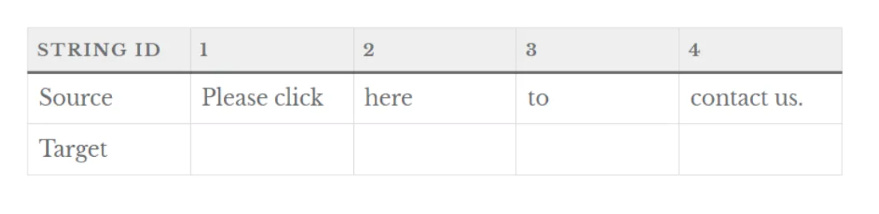

“Please click” + “here” + “to” + “contact us.”

The example above will output: Please click here to contact us.

For developers, this formatting might seem logical:

The word “here” is isolated because it will be turned into a hyperlink.

The final part “contact us” is separated so it can easily be swapped out with other phrases—like click here to purchase or click here to start now.

However, while this modular approach works in code, it creates challenges for localization, where sentence structure and word order can vary significantly between languages.

This would be presented to the translator as 4 separate segments.

Why is this problematic? Let’s look at Turkish. This is how the word order changes in Turkish:

Concatenation is one of the most common i18n pitfalls in software development. It often starts as a simple way for developers to assemble strings, but it quickly leads to untranslatable or grammatically broken text in many languages.

Concatenating strings in code might feel convenient, but in multilingual applications, it's one of the top causes of broken translations and poor user experiences.

Why Developers Use Concatenation

Let’s look at the common causes:

1. To Save Time or Avoid Repetition

"It’s just faster to build the string dynamically."

❌ Bad Example:

const message = "Hello " + userName + ", welcome back!";

Why It Fails:

Some languages change word order, gender, or formality.

This structure can't be reordered properly in translation.

✅ Solution:

"welcome_message": "Hello {{userName}}, welcome back!"

t("welcome_message", { userName });

✅ 2. To Reuse Static Labels

"We already have translations for 'You have' and 'items', so we’ll just reuse them."

❌ Bad Example:

const message = t("you_have") + count + t("items");

💥 Why It Fails:

Word order varies by language.

Pluralization logic becomes impossible.

No context for translators.

✅ Solution:

"item_count": "You have {{count}} items"

t("item_count", { count });

✅ 3. For Formatting (Bold, Italics, Links)

"We want to highlight part of the sentence or add a link."

❌ Bad Example:

const message = "Click " + "<a href='/terms'>" + "here" + "</a>" + " to read the terms.";

💥 Why It Fails:

“Here” has no context.

Sentence can't be reordered.

Formatting is baked into logic — hard to maintain.

✅ Solution (React Example):

"terms_message": "Click <link>here</link> to read the terms."

<Trans i18nKey="terms_message" components={{ link: <a href="/terms" /> }} />

✅ 4. To Combine Units or Symbols

"We want to show amounts, currencies, measurements, etc."

❌ Bad Example:

const message = amount + " dollars";

💥 Why It Fails:

Some languages put currency before or after.

Currency format may use commas or decimals differently.

✅ Solution:

Use internationalization libraries that handle number formatting:

new Intl.NumberFormat('fr-FR', { style: 'currency', currency: 'EUR' }).format(amount);

Or:

"total": "Your total is {{amount}}"

t("total", { amount: formattedAmount });

✅ 5. To Build Sentences from Fragments

"We’ll let each UI element translate itself."

❌ Bad Example:

<p>{t("greeting")}</p><p>{t("name")}</p><p>{t("ending")}</p>

💥 Why It Fails:

Fragmented text breaks grammar and sentence structure.

Translators can’t see how the sentence fits together.

✅ Solution:

"greeting_full": "Hello {{name}}, thanks for visiting!"

t("greeting_full", { name: "Julia" });

Best Practices

Use full sentences or phrases in translation keys.

Parameterize values like names, numbers, or dates using placeholders (

{{value}}).Use rich text interpolation (e.g.,

<strong>,<a>) via libraries likereact-i18next.Avoid reusing partial strings — even if it seems efficient, it breaks translation.

Always provide full context for the translator.

Context & String IDs 🔑 One meaning = one ID

Same English, different meanings

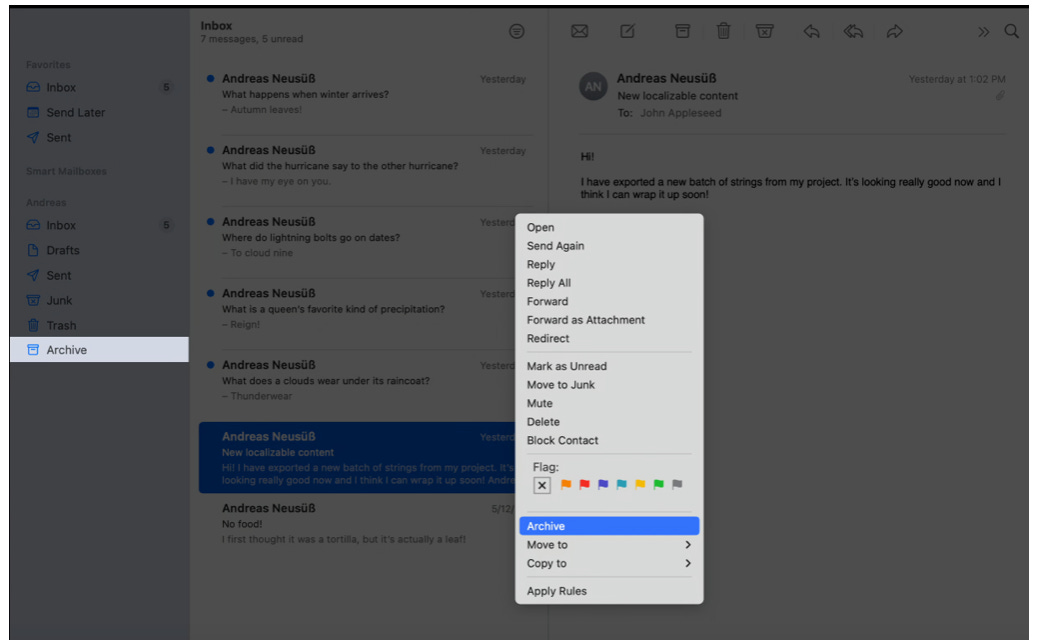

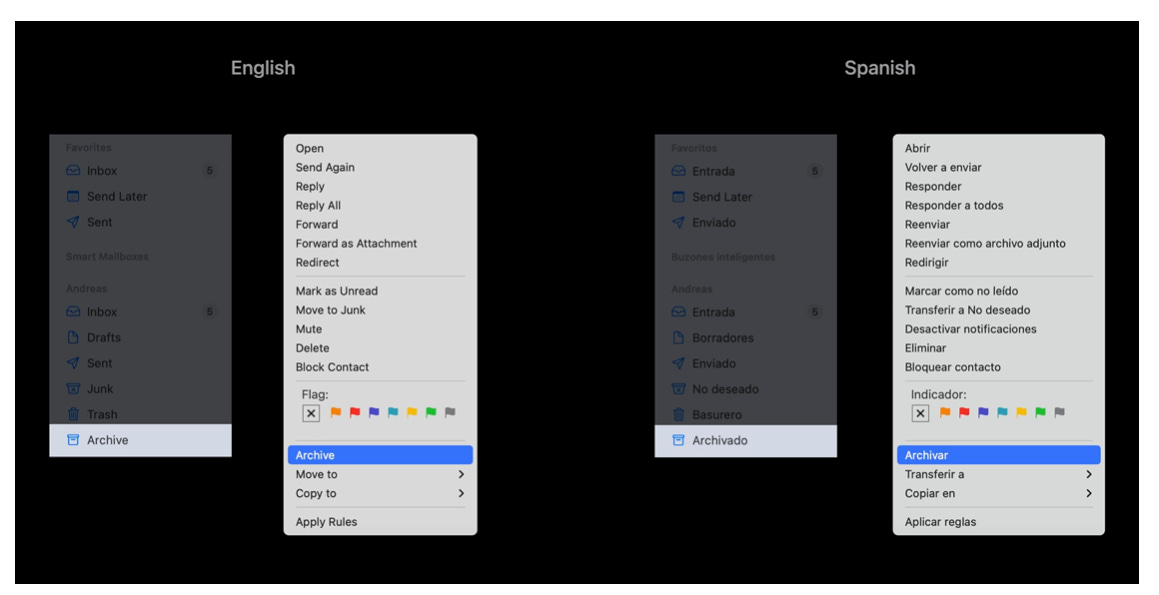

If you're using the Mail app on a Mac, you can right-click on any email and select "Archive" from the dropdown menu. This action moves the selected message out of your inbox while keeping it accessible. It's a handy way to declutter without deleting.

On the left-hand side, you'll also notice a mailbox labeled "Archive". This is the destination folder where all archived messages are stored.

Although both are spelled "Archive" in English, they play very different linguistic roles:

"Archive" (verb): the action you perform.

"Archive" (noun): the location or folder where those archived items are stored.

In localization, failing to distinguish these roles by not assigning unique string IDs means translators in other languages can’t reflect the correct grammatical structure or vocabulary. This can result in awkward or incorrect translations in the user interface.

Take Spanish as an example:

The action is translated as “Archivar” (verb).

The folder is translated as “Archivado” (past participle, used as a noun).

If both are forced to use the same string, Spanish (and many other languages) won’t be able to make that essential distinction. It may seem minor in English, but in target locales, this lack of context leads to poor UX and incorrect language use.

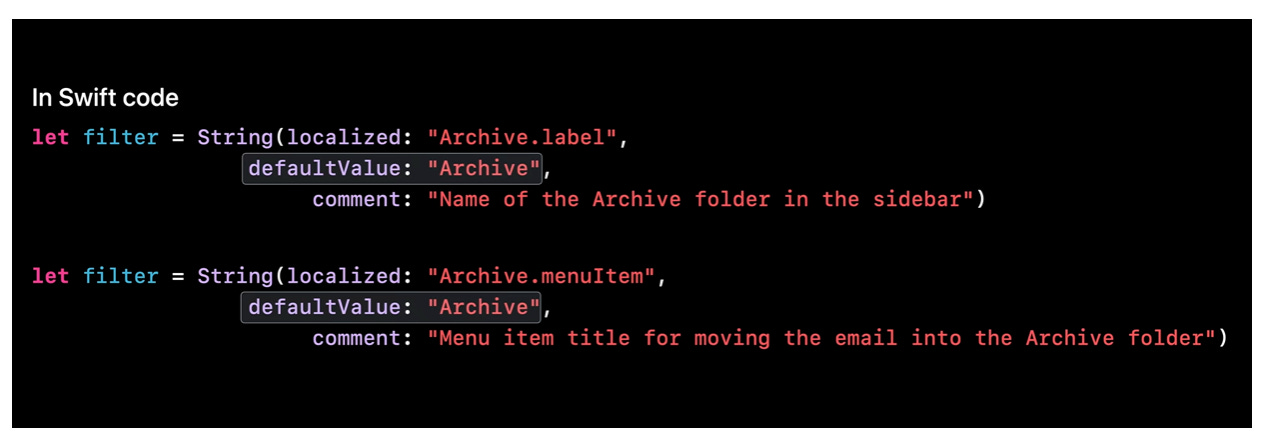

Pro tips for developers:

Always give separate string IDs to actions and labels, even if they look the same in English.

Add developer comments:

Adopt a clear, hierarchical ID scheme

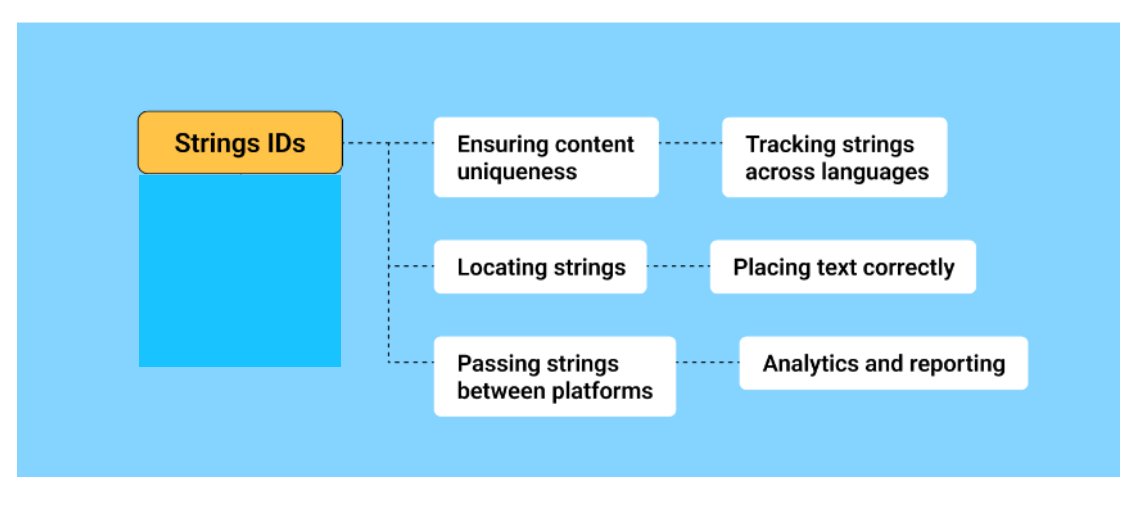

String IDs are more important than most developers think—they're not just technical labels, but essential tools for localization. A clear, unique string ID helps translators understand the purpose and context of a string. Without it, teams can’t tell whether “Archive” is a verb (the action) or a noun (the folder), leading to mistranslations and a poor user experience in other languages.

Variables - No variables after adjectives, articles, pronouns

Weather example

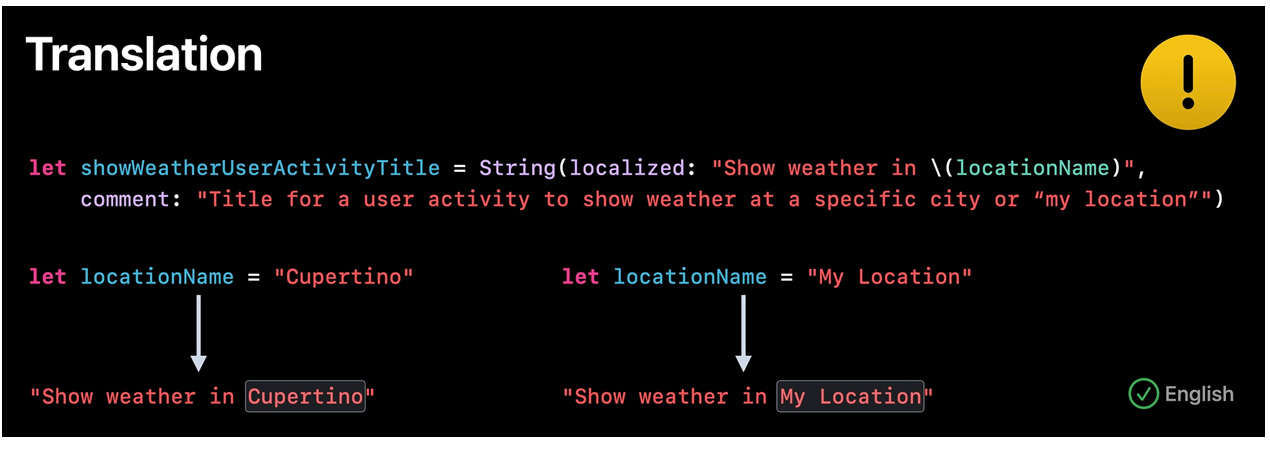

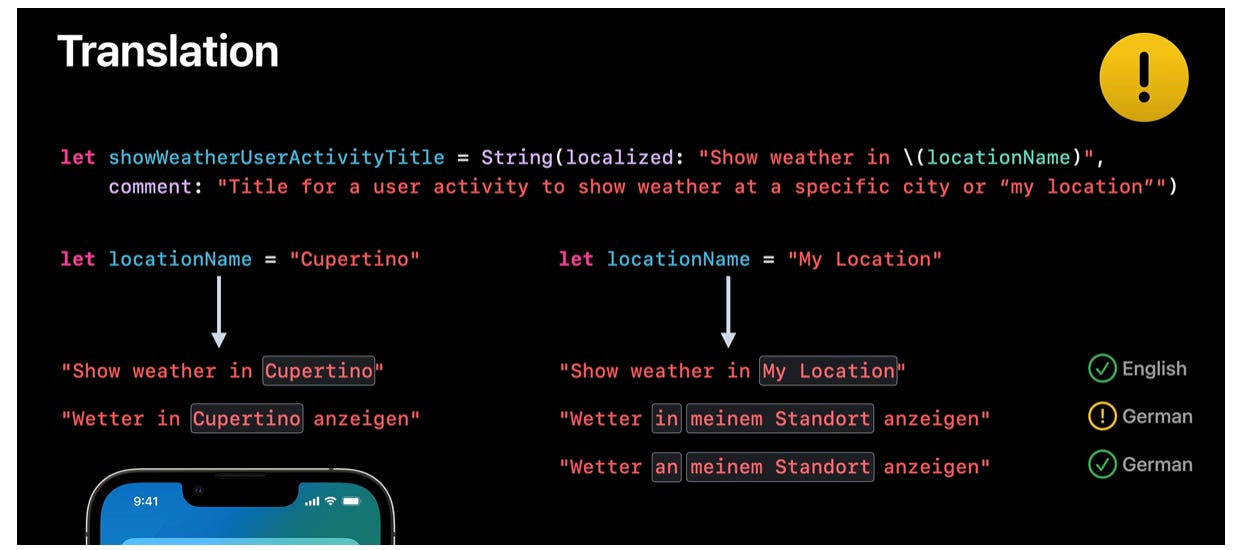

I’m sure you’ve used this feature on your iPhone: when checking the weather, you can either look up a specific place like “Cupertino” or simply tap Show weather in My Location to see the forecast right where you are.

How this might be implemented?

Looks nice and efficient in English. In other languages however, we might run into grammatical issues. Let’s take German as an example:

What's going on?

The original localized string is:

String(localized: "Show weather in \(locationName)")

This works fine when locationName is a specific city, like "Cupertino":

✅ English: Show weather in Cupertino

✅ German: Wetter in Cupertino anzeigen

But when locationName becomes "My Location" (a user-facing label for the current device location), the translation breaks:

✅ English: Show weather in My Location still makes sense.

⚠️ German: Wetter in meinem Standort anzeigen sounds off or grammatically incorrect.

✅ Correct German alternative: Wetter an meinem Standort anzeigen

The core issue

In German (and many other languages), prepositions change depending on the object:

"in Cupertino" → "in Cupertino"

"in My Location" → requires "an meinem Standort", not "in meinem Standort"

Because both “Cupertino” and “My Location” are being passed into the same string as if they were interchangeable, localizers can’t adapt the grammar properly.

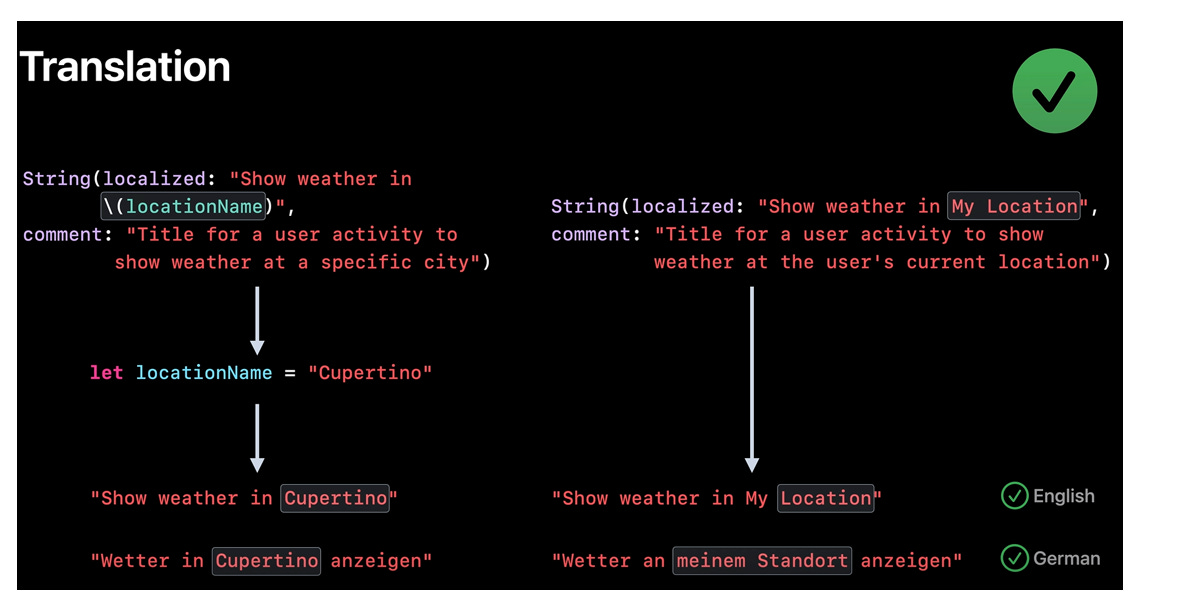

The solution is simple

You need separate strings for:

Specific city names →

showWeatherInCityGeneric current location →

showWeatherAtMyLocation

Each should have its own string ID and comment, allowing translators to write grammatically correct and natural-sounding translations.

I made this example to show you that inserting a variable had an impact on the entire sentence.

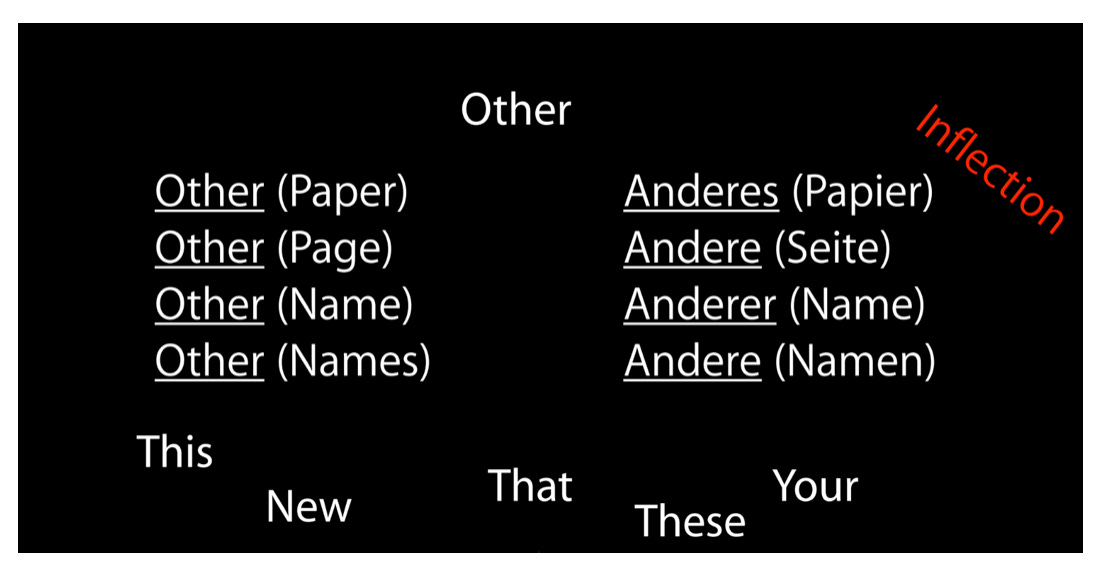

Joining strings might have surprising consequences in other languages. They might need to inflect the grammar or could have troubles with capitalization and knowing that beforehand when writing the code is difficult.

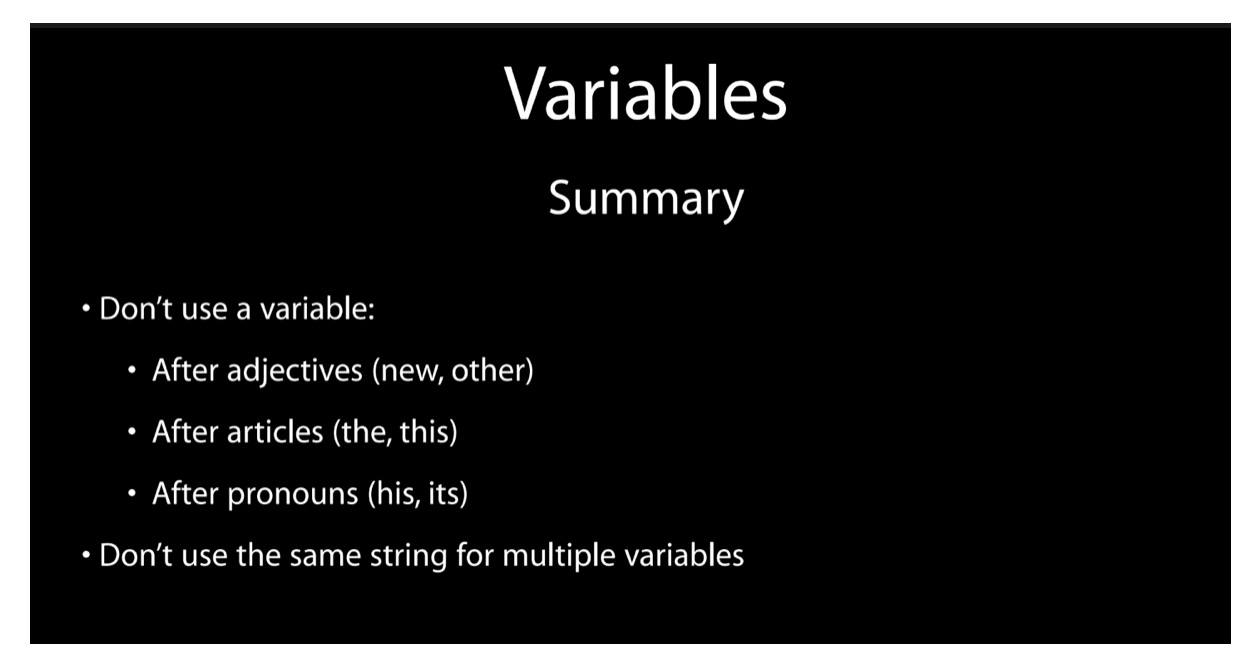

While variables are useful, there are cases where they can do more harm than good. Keep the following in mind when you are tempted to construct a string programmatically.

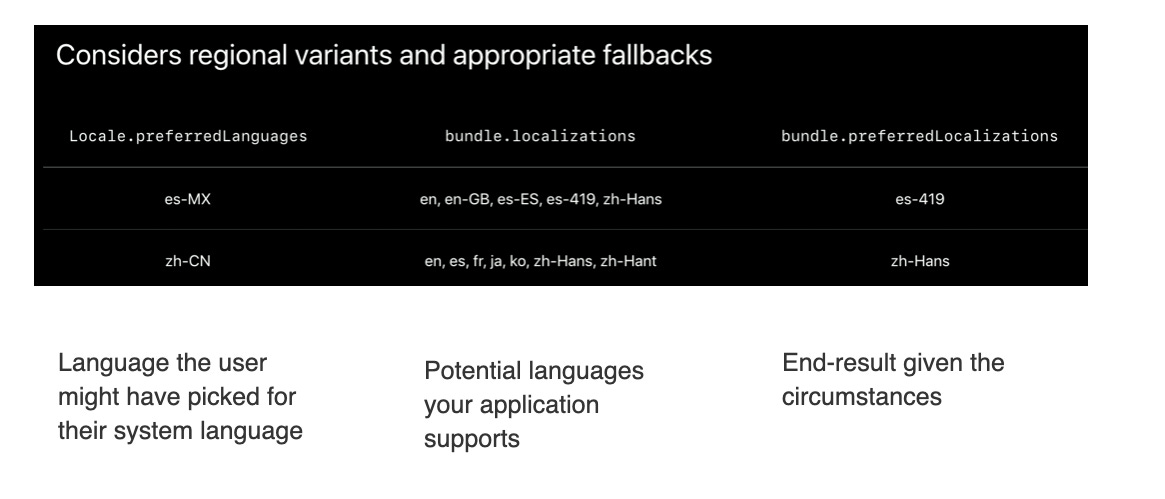

Regional Variants & Fallbacks

Having a fallback language strategy in place and allowing users to specify their preferred language and region is a must.

If a user's preferred language is not available, provide content in a widely understood language as a fallback.

Negotiate fallback order in code, not at runtime hacks.

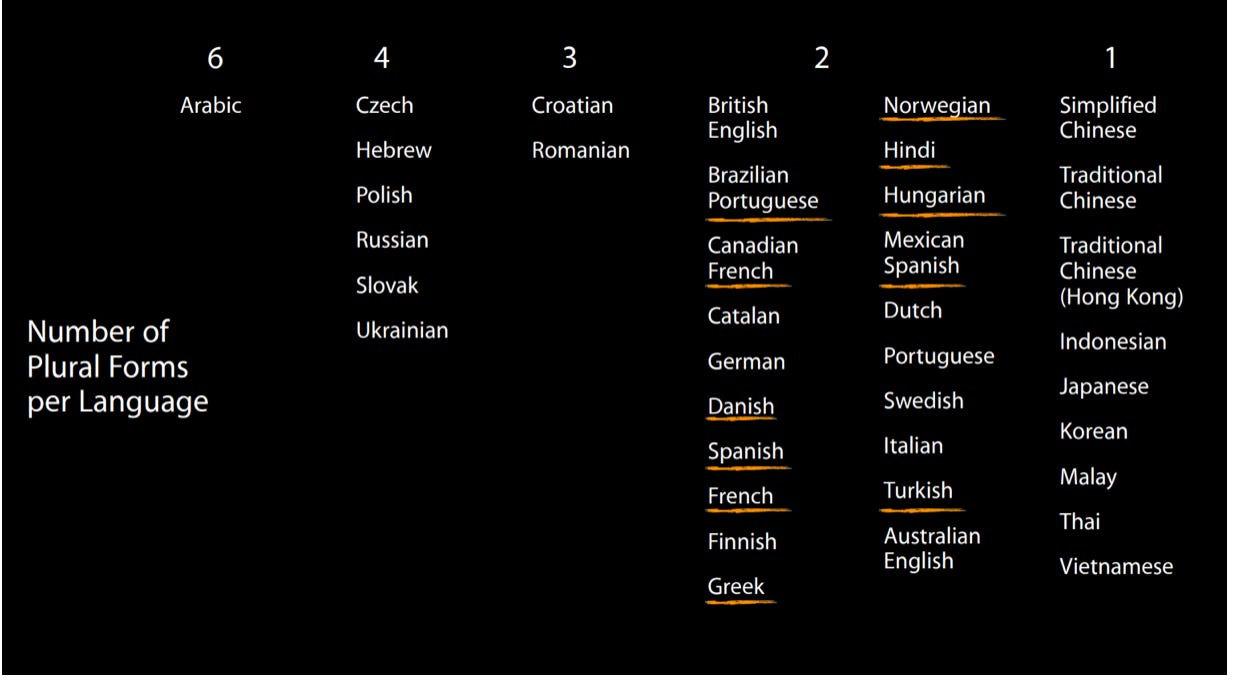

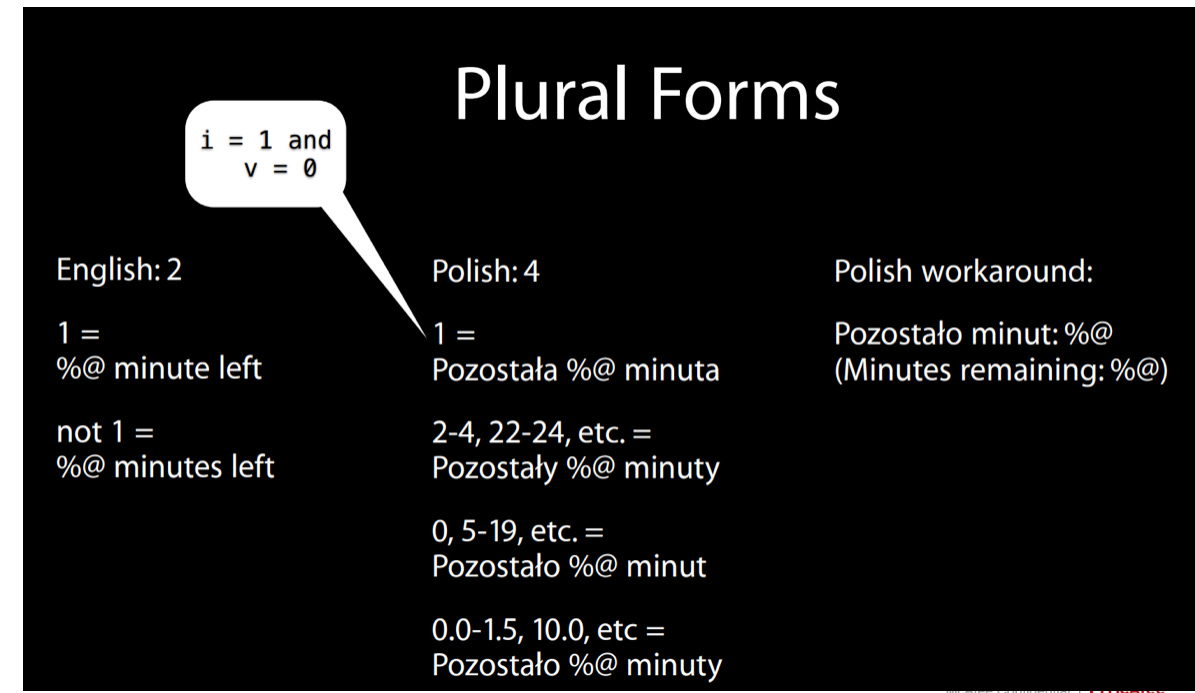

6. Numbers & Plural Rules

If your string does include a number, you should consider having variations for plural.

In English, pluralization is relatively simple—most nouns have just two forms: singular (month) and plural (months). But many other languages are far more complex. For example, Polish:

To handle this kind of variation, the ICU message format provides a powerful pluralization syntax. It allows you to define multiple versions of a sentence depending on the value of a numeric variable—essential in any localization workflow.

Sample syntax:

{num, plural,

zero {Selected {num} items}

one {Selected {num} item}

two {Selected {num} items}

few {Selected {num} items}

many {Selected {num} items}

other {Selected {num} items}}

The first argument (

num) is the variable whose value determines which version of the message is used.The second argument (

plural) tells the system to apply plural rules based on that value.Then come the plural categories—like

one,few, ormany—each followed by the message to display for that category.

For non-numeric values, you can use the select keyword instead of plural:

{gender, select,

female {She is here}

male {He is here}

other {They are here}}

🔹 The

otherkeyword is mandatory and serves as the fallback.

To determine which plural category a number falls into for a given language, check the official Language Plural Rules.

⚠️ Best practices:

Keep nesting to a minimum—it’s technically supported, but hard to maintain.

Always write full sentences in each plural case, not just the changing word. This gives translators the flexibility to adapt grammar properly in their language.

You can test your ICU plural strings using the Online ICU Message Editor. It’s a great way to preview how your messages will behave with different values and locales.

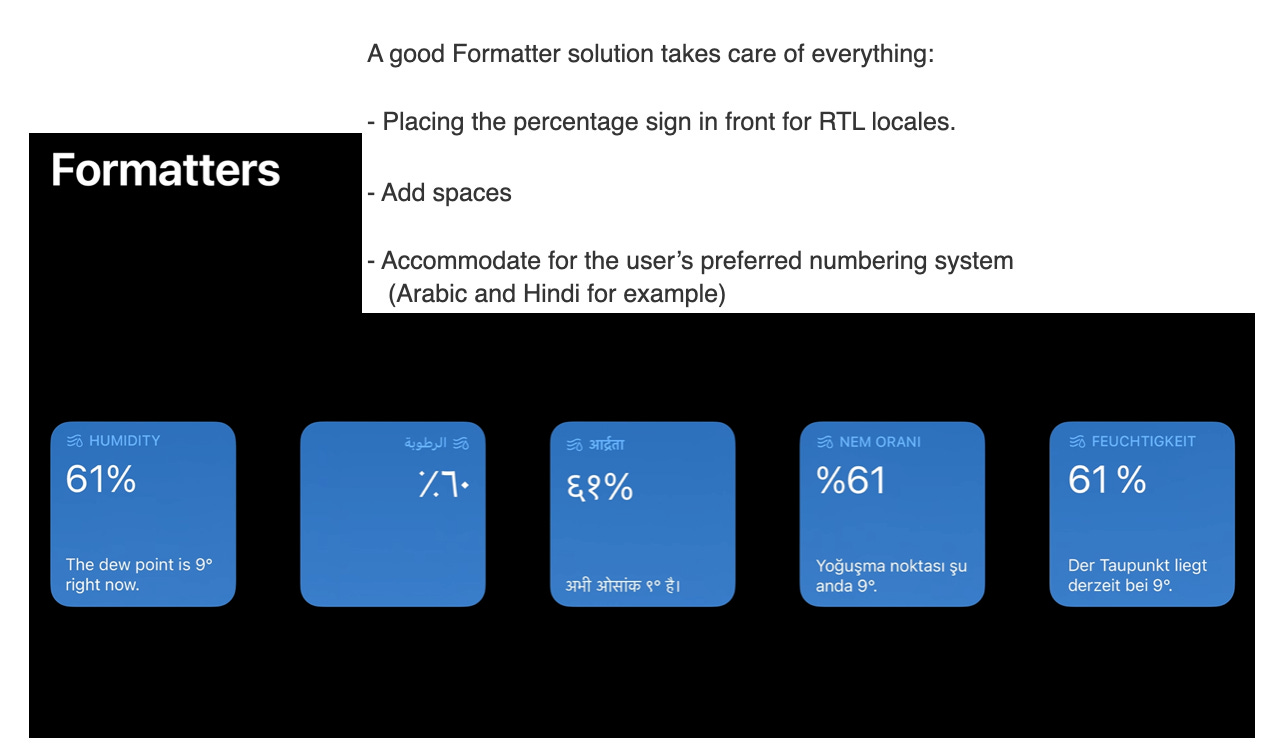

7. Data Formatters 📅 💰

If your string contains an unit in the sentence, like a duration, a time, a date, a price or percentage, you should consider using a formatter.

Never embed raw dates, times, numbers, or currencies in literal strings.

Why?

Because every locale has its own conventions for formatting data—and ignoring them can instantly break the user experience.

Instead, use built-in data formatters that automatically adapt output to the user's locale.

When working with internationalization, choosing a library that supports built-in data formatters is essential. These formatters handle dates, numbers, currencies, and pluralization according to each locale’s rules—so you don’t have to.

My Go-To i18n Libraries (And Why I Like Them)

If you’re building software for more than one market, internationalization (i18n) is non-negotiable. From plural rules in Polish to date formats in Japan, the complexity multiplies quickly once you step outside your source language.

Final Checklist for Engineers

One sentence = one string

One meaning = one ID

Be wary of variables (split when grammar can change)

Declare plural & gender rules in ICU or equivalent

Always use

Intl/formatters for dates, times, currencies, unitsComment every string with usage context

Internationalization is not about adding language. It’s about making space for it. Before a product speaks, it must be made ready to speak. That means building software that expects difference before it arrives.

We don’t hardcode. We separate text from logic.

“Hello” becomes %GREETING%, and every visible phrase is abstracted into a system of references. What was once a string becomes a placeholder for meaning.

Plural rules are not trivial. In English, we deal with singular and plural. In Arabic, there are five forms. If your code expects only one kind of plural, you will get it wrong—often and loudly.

Time is another form of language. The same hour does not mean the same thing in two places. We use standards like ISO 8601 and locale-aware formatting. And we remember that not all calendars are Gregorian.

Direction matters. Some languages read left to right. Others go right to left. BiDi text introduces complexity. CSS must adjust. Layouts must flip. Design must respond to grammar.

Text encoding is not just technical. It is political and historical. We standardize on UTF-8, but old formats still appear— Shift_JIS, ISO-8859-1. You must be able to read them, clean them, and convert them.

Flags are not languages. And en is not the same as en-US. Locales carry expectations—about spelling, formats, tone. A well-internationalized product treats es-419 and es-ES as distinct, because they are.

We use tools: ICU, gettext, i18next, CLDR. Not because they’re perfect, but because handling this by hand leads to chaos.

Internationalization is not polish. It’s not something you bolt on at the end.

It’s the groundwork that allows software to work outside the developer’s home country.

Done properly, it means your product can travel farther than you can imagine.

Done poorly, it means it never really leaves home.

In the next issue of The AI-Ready Localizer, I’ll explore how AI can help us proactively spot i18n pitfalls—missing context, hardcoded strings, ambiguous variables—so we can bridge the gap with dev teams early, before those issues become expensive fixes downstream.

What a great read! It makes me realize again how much I don't know.